I saw Short Cuts again, on the big BFI screen.

Which means that I’ve lived in London too long - it’s the second Altman season I’ve been to there. And much as I love his fluid and layered work - though not especially this one - for once I left a cinema thinking about the book (of short stories) rather than the film. Raymond Carver’s The Things We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Unlike Richard Yates, I’ve never been entirely convinced by Carver. Though If you’ve known me any amount of time then I’ll have told you often enough about how Carver and William Eggleston get mixed up in my head. When I read Carver I see Eggleston, when I look at Eggleston I feel Carverland is before me. It’s not synesthesia; more a case of sensibility. Despite the long shadows and warmth of the golden hour, what they share is an emotional coolness and a terseness perhaps; an American post-war world view that is conscious of maintaining a detachment from the subject matter. Something which in turn becomes entwined with the content of the work. So the photographs and the stories are about nothing in particular really, except nothingness. They share a language in discussing what’s not there - or rather what was but is there no longer. And maybe that’s why I can’t warm to either of them, despite being drawn to both.

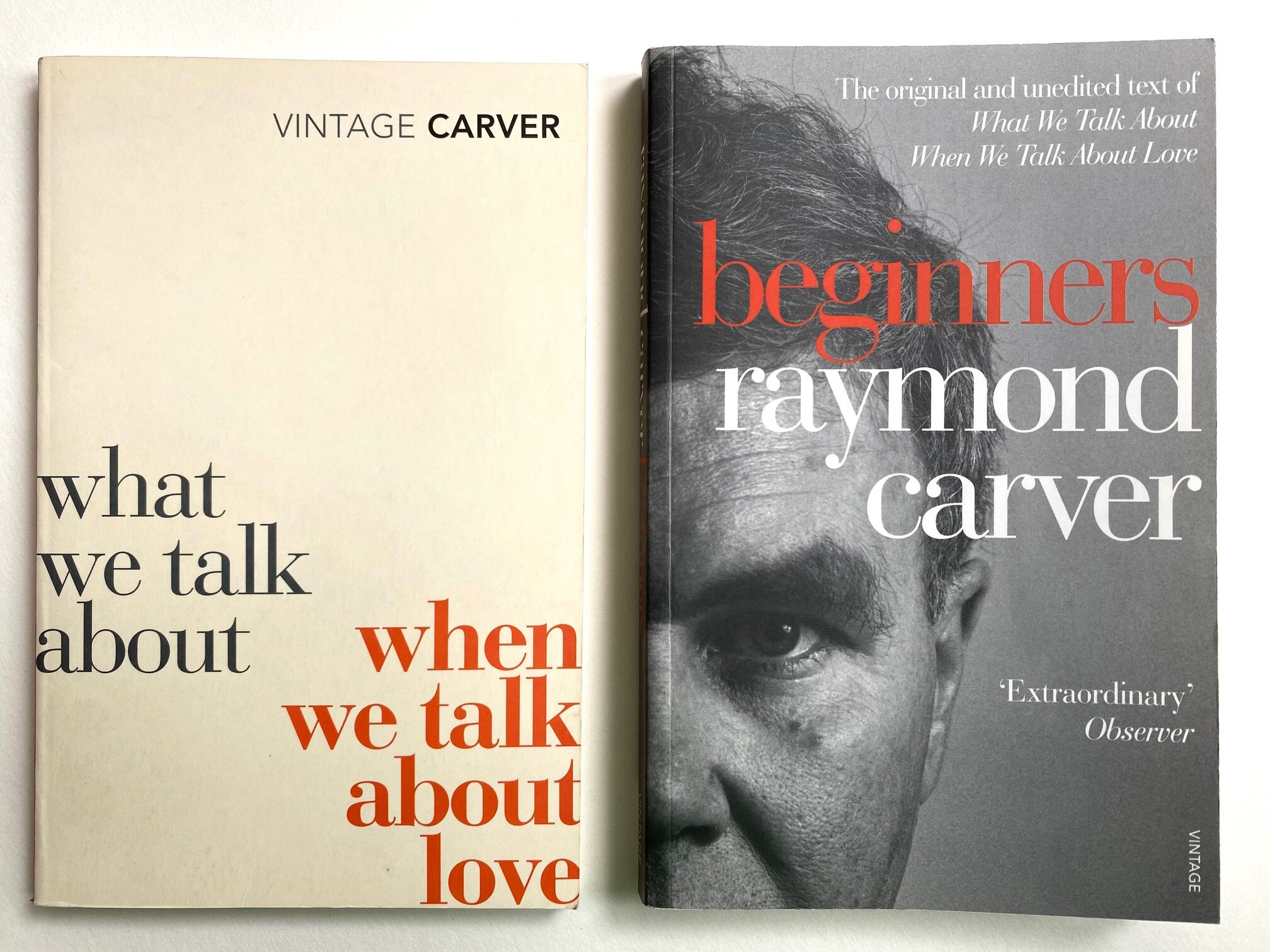

Though that wasn’t why I got my yellowed copies down from the shelf when I got home. Instead it was thinking about - the essence of Altman really - the importance of editing. I first read Carver after Short Cuts came out, and then about 15 years later in a different print, where the stories were so different from how I’d remembered them It felt as if I’d never read them at all. As it turned out, I hadn’t. There are two distinct versions of each story. Carver’s, in The Beginners, are about 60/70% longer than the Tess Gallagher-edited versions in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Yet hers are the ones we think of as his, with that short, punchy style. But she does much more than edit his words. She tells a different story, with her own.

Tell The Women We’re Going

One Sunday afternoon two bored guys, Bill and Jerry, leave their wives and young kids at the barbecue and go out for an aimless drive. Spotting two teenage girls on bikes they slow to talk to them before driving on to wait for them up ahead. The girls leave their bikes at the bottom of a hill and the men go up to look for them.

And then the story changes. Beginners has five pages (Gallagher’s version is only eight pages long, start to finish) of Jerry hunting down his victim at the top of the hill, raping her and then finishing with the trite apology before turning back to beat her head in with several rocks, as her friend waits back at the bikes for her. Bill then arrives and a drained Jerry rests his head on Bill’s shoulder to be patted as Bill cries.

In Gallagher’s hands there is no hunt, rape, violence or dialogue. Instead Bill gets to the top of the hill and sees the two girls with Jerry. Then the very last paragraph reads.

He never knew what Jerry wanted. But it started and ended with a rock. Jerry used the same rock on both girls, first on the girl called Sharon and then on the one that was supposed to be Bill's.

There’s nothing I dread more on a DVD cover than seeing the words ‘director’s cut’. Because they aren’t cut. Ever. It’s just the opposite - they’re extended versions of what you’ve seen, like the dreary drum solo on the album version that wasn’t on the single you loved. But then once in a while the editor can become the artist too. That’s a label I’d be glad to see.

artblog