I know. I should be glad really. A London Underground line that chooses not to tug a forelock at the Windsors and their ilk. What was once the East London Line - the branch I use - on the Overground has been retitled The Windrush Line after those dapper sons from distant shores. The languid stance, the zoot suits, what’s not to like? Except for the Irish amongst us there was something - that particularly English example of how some differences aren't really different enough.

While certainly reshaping London’s culture those sharply dressed young men were not the men who rebuilt Britain. Instead their days were mostly spent on the buses or in factories, as wives and sisters emptied the bedpans of a baby NHS. And they did this because someone else was busy rebuilding Britain, or England really.

Those men digging through the Empire’s rubble didn’t have as far to come but come they did. The Coffeys, McNicholases, Murphys, Kennedys, Clancys, Careys, Byrnes, Gleesons, and Fitzpatricks - the names on machinery and lorries on London roads every day since - would never be celebrated let alone acknowledged like this. Because when it comes to the Irish the English have always had a problem, one that veers from indifference, via bemusement - why are Irish names so hard to pronounce - to invisibility. As poor Churchill explained ‘We have always found the Irish a bit odd. They refuse to be English.’

It's not even about numbers either. In 1971 there were 350,000 of the Windrush generation in England while there was a million Irish (with six million left shivering on the Ould Sod). No, it’s what happens when difference is subtle but also sharply defined. So though we may pass as English, we really aren't. Despite the title of the blog being a Dubliners song maybe it was Bono who was closer to the truth.

We’re one, but we’re not the same

The Big Field

I think this may be my first piece of published artwork.

Uncredited, unpaid and so popular it returned as next year’s school annual cover. It proved to be then, at the age of 15, a fine introduction into the world of a freelance designer. That cover and those pages, dense with a forced normality, had sat ignored on a bookshelf until this morning. l’d had a request on Linkedin from someone in Belfast, working in NHS admin. He had an uncommon surname - in Ireland at least - though I had known one guy at school who shared it. So I did what I should never have done and allowed myself to dream that there may be some real work tumbling its way across the Irish Sea. That notion got no further than the first sentence on Messenger.

On a September day in 1974 in a perfunctary 1960s classroom we sat together for the first time. Alphabetically placed, one anxious boy per ink-welled wooden desk. Under the sleeves of our new blazers their old varnished tops bore the deep scars of furtively gouged nicknames, football teams and political affilliations. For most days, until O-Level choices weeded us out, that was our lot. Over the course new friendships formed and old friendships drifted away. But all me and my neighbour had really shared was proximity. So in the times since when l’d wondered where life had taken - or maybe, claimed - certain boys around me in that room he’d not been one of them.

Yet there he was, that other Mr H telling this Mr H about the changes at the school. How a floodlit, artificial pitch had replaced The Big Field, where balls had been kicked off the boundry walls of Crumlin Road prison on one side and the largest military base in Belfast on the other. He’d even returned as a governor - I don’t know which of us was more surprised - and his wife was a receptionist there. Yet I didn’t ask the one question I wanted to. In the 49 years since we first scratched our steel-tipped heels over that heavily polished herringbone floor what had brought him back there to think of, and contact me, now.

In the meantime though tomorrow will be another day to think of and maybe thought of. And perhaps even get some work.

A cup of cornflakes

Every day, every night of our lives, we’re leaving little bits of ourselves, flakes of this and that, behind. Where do they go, these bits and pieces of ourselves?

Raymond Carver

I went back to Belfast recently to sort out the boxes I’d cleared from my parent’s house; the same boxes I’d sorted out several years ago by abandoning them to the world of industrial estate storage. I had no idea what was in them let alone which bits and pieces would be coming back with me and while those symbols of a previous life remained unseen, there was still the present to be getting on with.

Housepaint, card, 1982

55cm x 85cm

Heading up to Tyrone and seeing my ever-jolly aunt, now in her 80s. An evening in the glorious Crown Liquor Saloon with my kickabout mate of more than 50 years, still his generous and content self. Seeing the peacelines slicing through Ardoyne and the Falls and how Belfast now shows itself to the world - plastic and rubber bullets produced from taxi drivers’ pockets and bounced off walls for the benefit of the startled tourists. Every street was a small and ghostly piece in a jigsaw of memory. Houses now stand on the corner where once clumps of scalp and bloody hair lay scattered as our school coach slowed on the way to the playing fields. Nearby a nondescript pavement that one afternoon was awash with the blood of a prison officer. A year older than me, he was killed as he waited at the bus stop where our scruffy footprints now stained the floor of the bus home. And then down into the city centre where the mothership of a rebuilt art college has eaten up the northern edges of a still fractured city centre.

Later, in the quiet greyness of a south Belfast retail park, I find my oversized boxes. What little they hold had been easy to ignore after all. Dreary Country & Irish albums (my mother’s), bloated early-80s 12’’ singles (her son’s), the Sacred Heart picture I was afraid to dump; two tiny gold-rimmed, shamrock-decorated wine glasses (now seeing nightly duty in London) and my limited art output from teenage years to art college. Work that had been or should have been well forgotten. Though one painting stood out, just not for its quality.

We were rarely in that main room in Foundation. Like a middle management away-day icebreaker we were to escape preconception by exploring limitation - using household paints and brushes on an absorbant unsympathetic grey card, we had 15 mins to paint the life model (who may or may not be wearing a solitary glove, it seems).

We were also the errant child that wasn’t allowed near the grown-up Belfast campus. Exiled to the loughshore outside the city, we huddled in freezing jacked-up portacabins on the edges of the Ulster Polytechnic playing fields. Both our tutors were painters. Denis McBride, heavily moustached, tweed-jacketed and in his early 40s, and Moore Kenny, younger and balding but with long unkempt hair that hung over his shabby greatcoat. They’d occasionally swing by to say a few words before heading back for another smoke and cup of tea in their snug brick office. Like a bad 70s cop show we thought they’d been teamed together through an administrative error or as a punishment by their brutal academic bosses.

Of the two Moore was the more sympathetic, with an empathy and a gentleness that wasn’t obvious in his ebullient, swaggering pal. I‘d no idea then how 3rd-level education worked and, despite going to Chelsea a few years ago, I still don’t. So when he’d disappear for long spells it meant little. Until one day we heard that the peelers had picked him up, walking along the nearby 10-lane-wide motorway. In his pyjamas and holding a mug of tea he was carted off in their heavily armoured Landrover to the pyschiatric hospital outside Belfast.

Months after, just as I’m leaving the painting exercise, Moore appears. There’s some work out on a table and he zooms in on an innocuous black and white monoprint. He’s talking at speed, elliptical comments, over and over. The hidden symbols, their sexual undercurrents, that speak to him and him alone. And the violence there too - why can’t we see that? He’s becoming more animated. Big gestures now, the coat flapping, a mental energy becoming physical and the faces of the few girls nearby have changed from wary to scared. I’m not too sure about it all either. Then from nowhere he produces a cup full of cornflakes which he scatters over the print as he goes quiet. And you’re 19 and think, well, maybe that’s just what happens at art college. Even in Belfast.

We never saw him again.

Two years later I’m at the art college in Belfast and he is walking down the corridor towards me. We stop to speak but from the few words he says I’m aware there’s still an edge of unpredictability there. As we part I wish him well.

A month afterwards he walks across the dual carriageway and into Belfast Lough.

Yes. Where do they go, these bits and pieces of ourselves?

That summer feeling

I didn’t imagine it. When I was very young the summer holidays in Belfast really did go on for ever (almost nine weeks certainly felt like forever). And the strangest thing was the kids TV; or really the absence of it. Every year the BBC filled our empty weekday mornings with dubbed (De Lane Lea - thanks Stuart Maconie) French, German or exotic international co-productions (basically involving Yugoslavia) which, like a butterfly, would flutter brightly before disappearing until the same time next year. There was a wistful Robinson Crusoe, some confusing White Horses, and a galloping Flashing Blade. But why start so late into the holiday that they rarely got past the caterpillar stage before I was back kicking a football round my sloping playground? By the time I found out I was at Secondary school and too old to care. The BBC believed only English school children needed their summer mornings filled, some three weeks after their Irish and Scottish peers had started to make their parents long for the return to the school routine. Anyway in amongst these distant curios was a zippy animation, Herge’s Adventures of Tintin. Bursting with imperialist bluster there was no room for a bewildered young Belfast viewer to enter, let alone engage with, whatever was going on. Despite the young shark-fin headed journalist’s extensive travels there was little for us to discover. So it’s strange then that years later my house is full of beautifully realised cast models and hand painted pewter figures, lifted from those tedious stories. But it’s not Tintin I like, or a link to my childhood summers. Instead it’s the objects themselves.

When I see a Celtic top being worn - which is quite often - I know it’s being worn as a sign of support for Celtic and not some aesthete showing their appreciation of the shirt itself, great as it is.

So this last week I’ve spent a lot of time on an image-based painting (there’s a particular kind of satisfying engagement in making and looking at representational subject matter). It turns out it’s an image of me. Though it’s not a self portrait - it was just a poor printout I rediscovered when I was tidying up, and I liked its rough photocopy quality. The subject really then is the degraded visual aesthetic and the process of stencilled marks thar follow in the painting. Really it’s not what the original image depicted, it’s how that image was depicted. But I know no one else will see that. They’ll see a face, mine. And I also know, like the never-ending school holidays, that when we go looking for meaning often all we will find in its place is the mundane.

Night moves

As a man who glides like a whale on rusty castors I’ve always envied good dancers.

Maybe it’s the lightness of movement, maybe it’s the certainty that comes from not having to think when you are just busy doing. There’s an ambivalent relationship men have with dancing too, as well as with drawing; activities that are neither obviously masculine nor feminine. For most men, moving and making exist in a parallel world, so while they may respect other men who can dance or draw, they don’t feel those qualities are extensions of themselves.

Anyway, dancing. The strutting peacock, that individual flourish in the midst of collective activity. If you’ve ever seen those clips of scrawny northern white working-class men swirling and spinning in super-tight tops and super-loose trousers at a Wigan Casino Northern Soul night, then you’ll know that for them 1970s masculinty was up for grabs. A night out with your mates was no longer 20 B&H, heavy boozing and a good dig at the end of the evening. Instead there you were with thousands of other peacocks - off the booze but on the pills - spending the entire night showing off. Not to impress women either - those that were there were there to compete too - but to impress yourself and your peers. I worked with one of those fine movers, Paul Mason, whose brief doucumentary about his dancing days is well worth a view.

So a couple of years ago I sat up, revisiting Saturday Night Fever. Top choons, top moves. And there he was, the preening John Travolta as Tony Manero, a man very much of his time and place (something I like). Dance floor shapes apart though, the film is of its time in another way. I’d forgotten what a rancid movie it is and how the music and dancing distract from that. A gang rape in the back of the car as a nonchalant Manero sits in the front (she deserves it though, so why care?). Later, when he rapes the only strong and independent character in their dull circle, his victim is the one who has to leave town. Then at the very end when he drives over to see her it is not in a rare moment of self-awareness, but so she can comfort him for all he’s been through, the poor dear. It’s an empty and hateful film.

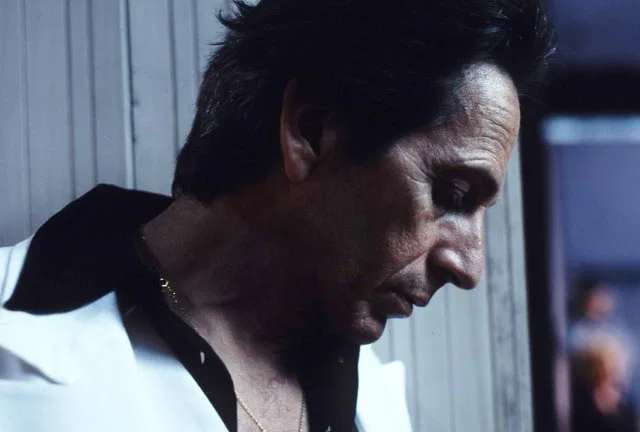

Tony Manero

Pablo Larrain, 2008

Now I don’t know how TV programming works, but I’ve often felt it’s similar to - from experience - how policing works. There’s no innate understanding or willingness to move in and around a subject, to weigh things up, to strike a balance. Instead it’s a matter of proximity and convenience. So a tenuously themed night’s entertainment saw a Chilean film follow because it was called Tony Manero. After all who cares what is on at 1:00 in the morning anyway.

Annoyed at Saturday Night Fever’s self-pitying Manero I stayed up to see what Santiago’s version was like under Pinochet’s rule in 1978. Martial law and state murder gangs are merely the background to a middle-aged sociopath and his Travolta obsession; one whose world revolves around getting his white-suited self onto a TV talent show. In one of the most memorable films of the last 20 years an amoral man kills, steals and expolits any opportunity or anyone he can to get that chance. Obssessed, charismatic, vain and ruthless Manero also produces, squating, a genuine moment of dirty dancing before the film finishes with a bus ride home.

He’s hateful certainly but at least that’s the point here. And that man’s castors were beautifully oiled.

We all know this is nothing

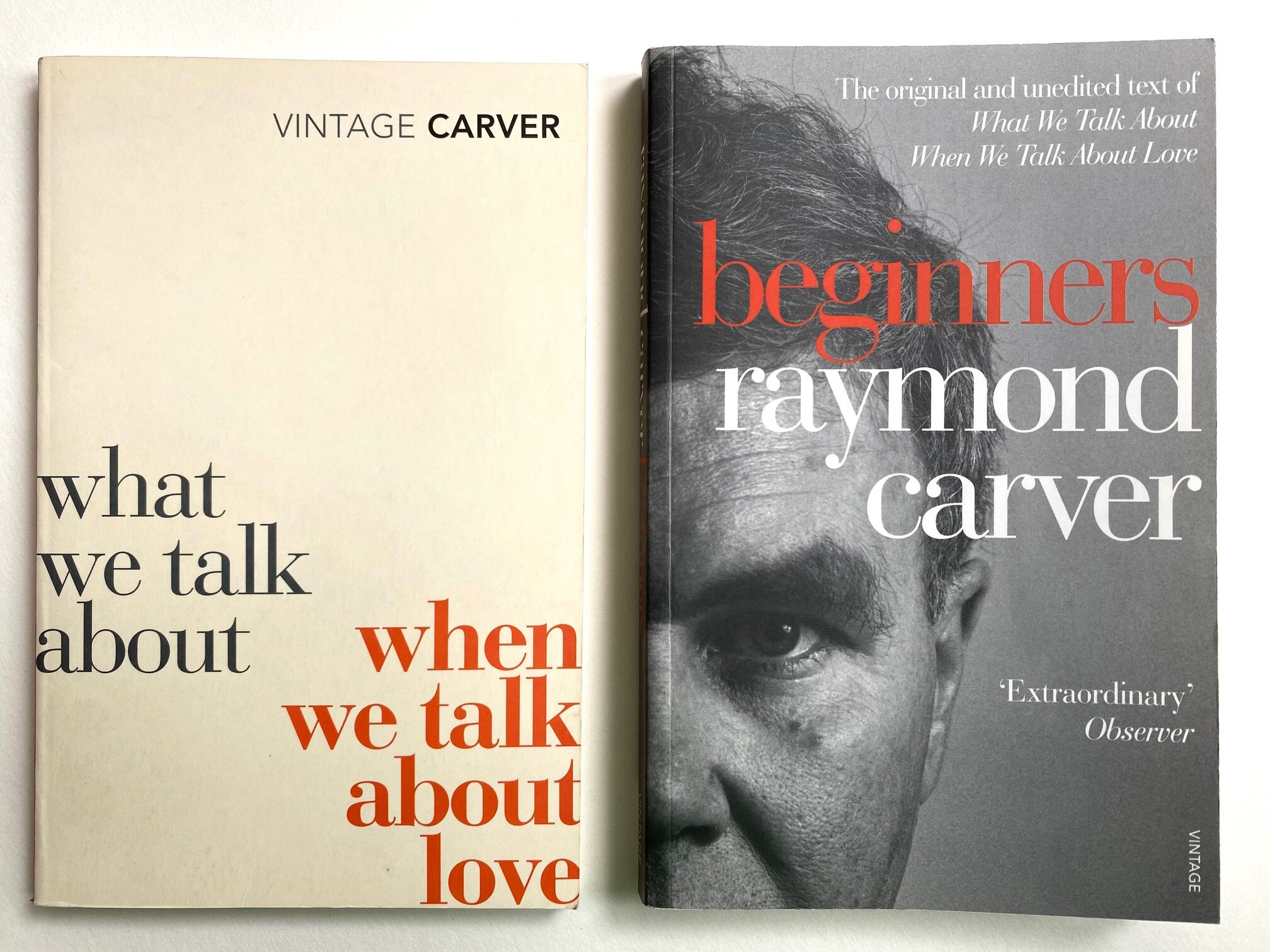

I saw Short Cuts again, on the big BFI screen.

Which means that I’ve lived in London too long - it’s the second Altman season I’ve been to there. And much as I love his fluid and layered work - though not especially this one - for once I left a cinema thinking about the book (of short stories) rather than the film. Raymond Carver’s The Things We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Unlike Richard Yates, I’ve never been entirely convinced by Carver. Though If you’ve known me any amount of time then I’ll have told you often enough about how Carver and William Eggleston get mixed up in my head. When I read Carver I see Eggleston, when I look at Eggleston I feel Carverland is before me. It’s not synesthesia; more a case of sensibility. Despite the long shadows and warmth of the golden hour, what they share is an emotional coolness and a terseness perhaps; an American post-war world view that is conscious of maintaining a detachment from the subject matter. Something which in turn becomes entwined with the content of the work. So the photographs and the stories are about nothing in particular really, except nothingness. They share a language in discussing what’s not there - or rather what was but is there no longer. And maybe that’s why I can’t warm to either of them, despite being drawn to both.

Though that wasn’t why I got my yellowed copies down from the shelf when I got home. Instead it was thinking about - the essence of Altman really - the importance of editing. I first read Carver after Short Cuts came out, and then about 15 years later in a different print, where the stories were so different from how I’d remembered them It felt as if I’d never read them at all. As it turned out, I hadn’t. There are two distinct versions of each story. Carver’s, in The Beginners, are about 60/70% longer than the Tess Gallagher-edited versions in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Yet hers are the ones we think of as his, with that short, punchy style. But she does much more than edit his words. She tells a different story, with her own.

Tell The Women We’re Going

One Sunday afternoon two bored guys, Bill and Jerry, leave their wives and young kids at the barbecue and go out for an aimless drive. Spotting two teenage girls on bikes they slow to talk to them before driving on to wait for them up ahead. The girls leave their bikes at the bottom of a hill and the men go up to look for them.

And then the story changes. Beginners has five pages (Gallagher’s version is only eight pages long, start to finish) of Jerry hunting down his victim at the top of the hill, raping her and then finishing with the trite apology before turning back to beat her head in with several rocks, as her friend waits back at the bikes for her. Bill then arrives and a drained Jerry rests his head on Bill’s shoulder to be patted as Bill cries.

In Gallagher’s hands there is no hunt, rape, violence or dialogue. Instead Bill gets to the top of the hill and sees the two girls with Jerry. Then the very last paragraph reads.

He never knew what Jerry wanted. But it started and ended with a rock. Jerry used the same rock on both girls, first on the girl called Sharon and then on the one that was supposed to be Bill's.

There’s nothing I dread more on a DVD cover than seeing the words ‘director’s cut’. Because they aren’t cut. Ever. It’s just the opposite - they’re extended versions of what you’ve seen, like the dreary drum solo on the album version that wasn’t on the single you loved. But then once in a while the editor can become the artist too. That’s a label I’d be glad to see.

Psycho

Alfred Hitchcock, 1960

And the moon rose over an open field

Phoenix, Arizona, Friday December 11, 2:43pm.

On a sunny winter afternoon the camera pans and zooms to a half-open hotel room window. Through the darkness under a partially raised venetian blind a woman in her underwear is lying on the bed. At the end of a stolen lunch hour, her lover is dressing to leave.

When back at work she takes a chance. Stealing an envelope stuffed with $40,000 she flees town to drive to her boyfriend’s in California. As night falls she stops. The sharp morning light reveals her parked in front of a treeless hill, which belongs in an Edward Hopper painting (who is also referenced later in main house)

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78330.

A suspicious cop raps on the window and wakes her; anxious, she moves off but he follows. Later in the cramped dark toilet of a second-hand car dealer she takes cash from her handbag, buys a new car and drives the straight roads on into the night. Violent rain and slashing windscreen wipers mix with the guilty voices of conscience, as glaring headlights grow ever bright and harsh on tired eyes. The shrill and insistent Bernard Herrmann score builds before fading to one long sombre note as she pulls off the highway to the haven offered by a glowing motel sign.

There the twitchy owner offers her tea and sandwiches. In the parlour at the back of the office they sit opposite each other, her leaning forward on the edge of the chair. Around them extended wings of stuffed birds mark the walls with long shadows. Although she isn’t fully at ease she is very much a woman of the world; his gauche and over-talkative tics are the opposite of her sexual confidence. She’s in control and knows her game, and also that he has yet to play it. So while she may be guarded, he is nervous with edgy small talk about his mother. But then he steps outside the rules of conversation and convention, as if they had never mattered to him.

You’ve never had an empty moment in your entire life, have you?

Because by god, he’s had plenty. Jolted, she continues, unable to gauge the sudden shift in power. Like hearing a record playing backwards, it becomes clear that we’ve misinterpreted everything. The linear narrative, the moral primer and the certainty of the protagonist’s world is of no interest here. So soon when he spies on her changing, before later yanking back the plastic curtain as she showers - and under flat uncinematic lighting stabbing her to death - he will take away not only her life but also the certainties of what we have been watching. Up until that point the transgressions - the underwear - twice - a sexually active and unmarried woman, the theft, the betrayal of her boss’ trust, and not least the first appearence in American cinema of a toilet - have been part of a conventional morality tale; one where guilt leads via conscience to punishment, and so redemption. Knowing what the rules are and how they have been broken, she will return the money and accept her fate; the predetermination of Presbyterian America.

But that’s her understanding, not his. Just as she stole the money by chance and turned off the road by chance, she will also die by chance. A good opportunity, a bad opportunity, is still an opportunity. A failing motel and $40,000 in her bag should be plenty of motive, but it’s meaningless. Instead, he will kill her because he wants to and because he can.

Impactful as they are, Hitchcock’s ghoulish elements and set pieces are like distant explosions. It’s only later that the aftershock hits. At the end of the film there are pat psychiatric explanations which feel like they have been grafted on by studio executives, afraid of the moral emptiness at the heart of the film - a killing without explanation. For in a culture of biblical moral certainty there can be nothing more shocking than an amoral act. There can be no good and no bad, if there just is.

More than 60 years later Psycho still retains a powerful truth. While the myth of the western frontier runs through the film, all that awaits when we turn off the road is the emptiness of Hopper’s railways, the restlessness of Hank William’s Ramblin’ Man or the cold horizon viewed by Paul Simon through the window of a Greyhound bus.

Kathy, I'm lost I said, though I knew she was sleeping

I'm empty and aching and I don't know why

Seek and ye shall find. Yes. But what, exactly?

William Eggleston, From Dust Bells, Vol 1

Memphis, c. 1965-68

Distant voices, still lives

For the lovers of the 1971 American road movie Two Lane Blacktop - me - tarmac and cities are the stuff of existentialist dreams. From a montage of films, photographs, writing and music ideas of motion and place swirl in your mind long before you - if you ever do - arrive at your destination. These places, real and imagined, shape an understanding of not just the world around us but also the world within us.

This last year the streets and spaces of London have never been more empty and yet I’ve never felt more a part of them. The closed drab doors and unwashed widows, the padlocked shutters and dusty cars, the half-open gate, the drawn curtains with the dim glow of a life being lived elsewhere. All the clouded layers of noise and bustle and distraction have faded like the early haze of a hot summer morning.

There is a lazy narrative served up weekly in Sunday magazine back pages. It is one of escape from the teeming and claustrophobic city to the open and spacious countryside. To be away from everyone and everything is our natural state, a return to the serenity of the Garden. There, absence will allow us to be who we really were meant to be. Though the stillness of the countryside is not one of the future but of a past; one where space is not inviting but constraining. Heavy with the weight of received opinion and deference all choices have already been made, especially for an outsider.

Two cyclists @ Coal Drops Yard, Kings Cross

First lockdown

I went on the Overground to Hoxton last week to get some spray paint. In this now empty city crossing a deserted street or looking out through a train or bus window - the sitting, the detachment in being transported - creates a reverie where we are free to look, to explore, and to dream. As Susan Sontag wrote, we become a tourist in other people’s reality and so, eventually, in our own. And now it is the very absence of those people which allows cities to reveal themselves to us and then us to ourselves. Drawing a space where everything seems possible, the quiet and exhilarating stillness becomes our inner landscape. Like the dry autumnal leaves on an empty tennis court, for those who have ever spent their day staring out a window at nothing in particular or felt the warmth of the sun in an Eggleston photograph, then this is what dreams, and we, are made of.

Wordy rappinghood

What are words worth?

I like them. Words.

Their rythyms, and the particular satisfaction that comes from seeing an apt word - like traverse, say - perfectly placed in a sentence. But when it comes to art there’s one I struggle with - abstract. As a noun, verb, or adjective it essentially means the same thing; a summary. Yet when referring to a painting it describes something which is non-pictorial or non-representational. And I don’t get why that is. Like orange and spicy, they’re just different things.

In the summer of 1994 I was stuck in an overpowering and disinterested Dallas - where all galleries, shools and hospitals have either Methodist or Presbyterian above their doors - covering the World Cup for Reuters. Escaping the media centre’s plastic lunches I got an air-contioned taxi to the other side of town. Gliding through one dazzled and soulless street after another, everywhere felt like nowhere. Only the bow-tied Nation of Islam paper sellers were hardy enough to stand under the high and unforgiving sun.

Arachne (A Sibyl)

Velazquez

1644 - 1648

Half an hour later I am in front of a minor Velazquez. I move closer, look and then step back. This goes on for a good ten minutes. I’m transfixed by a small pink blob of paint on a fingernail. It has no reason to be there - it doesn’t describe the form and it’s also too bright - and despite all the fabulous brushstrokes around it, it’s all I can see. It’s a blob of paint. It’s a fingernail. Yet clearly it’s both things at the same time. That mark describes the experience of being a mark as much as it describes a part of a finger. So although this is representational art it is as much about reduction and abstraction as any Mark Rothko is some 300 years later. Perhaps the real difference is that while one sets out to describe the outer world, the other portrays the inner. Artistically sated but now hungry I head back in the frigid taxi air. On the other side of the tinted windows a sluggish city trudges by.

Concrete words, abstract words

Crazy words and lying words.

The Tom Tom Club knew their stuff alright.

Heaven lies about us

Transparent spray paint, canvas

76cm x 76cm

2021

The joy of painting

I’ve been struggling.

My back is aching and it’s all my fault. Having had a working life in design should be an advantage in making geometric art. But instead it’s ended up reducing me to the role of being my own technician, bent over a table all day.

A painting can be many things. When you see a Bob Ross or a Howard Hodgkin - frame and all - you know you’re seeing a painting. But look at Roy Lichtenstein’s later work and it’s as smooth and flat as an ironed-on transfer; graphic, clean and so precisely applied the painting style reinforces the detached take he has on his work. I’m unsure if knowing that it’s painted and appreciating the labour and the skill spent in disguising that fact means we respond to it differently than if it were just a giant print. But then why else lean in close unless it’s to see that texture of brushstroke on canvas, those wee blemishes that let art breathe, before we lift our Tote bag on the way out.

I’ve spent many Covid days in the studio, calculating, measuring, masking, lining up and spraying. And yet the best I can hope for is to have a bigger version of what I’ve seen on my laptop. Everything is already decided before I start and that’s been my problem. Anything that happens from then on just looks like a mistake. The result is that I’ve been busy removing myself from my own work.

Like a contrite Boris Johnson, happy accidents don’t exist. Instead there are only unimagined consequences which appear in the making; recognising and responding to them then takes the piece in a new direction.

Recently it’s been the bits around the making that have inspired; the overlapped and layered edges of masking tape, the unaligned gaps between the stencils, the irregular patterns and uneven spraying. All have a life and unpredictablity that the designs I’m making - or really applying - don’t. So, while the grids are there to hold the marks of the making and to serve the work, they shouldn’t dictate it.

And although the sellers of Ibuprofen may not thank me, I’m hoping at least my back will.